This past summer, the summer of 2016, I was in the United States for the Fourth of July. Because I typically studied abroad in the summer, being in-country for our most patriotic of holidays was most certainly not a guarantee, not even the norm. Yet, on July 4th, 2016, I was grilling out at a friend’s apartment in our nation’s capital, Washington D.C.

Well, technically, Tysons Corner, Fairfax County, Virginia, but close enough.

I was happy to be with people that I loved, in the country of my birth, on this day. Dare I say it, I even felt a little pride for my nation.

We had a lot going for us. In 2015, the landmark Obergefell v. Hodges decision made love the universal language that we were all now free to speak. The United States Treasury Department announced that Harriet Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson on the front of the twenty dollar bill. And Hilary Clinton was the first woman to be a major party’s presumptive nominee for President of the United States of America.

I suppose now is the time for a bit of political PSA: Regardless of how you feel about the current state of our national affairs, it is important that we look to the gains that we have made instead of dwelling on the staggering regressions we are now experiencing.

Because things are changing. The WWF reports that, for the first time in a century, the number of wild tigers that exist in the world has increased. And who doesn’t want to live in a world with more tigers?

As a young, optimistic American, I am choosing to see the positive changes that my country has embraced within the lifetimes of my grandparents, my parents, and me. I can assume that America as a whole no longer wishes to be judged for the mistakes of its past. While those with privilege remember the post-WWII era and what followed as “The Good Ole Days,” rosy retrospect does not paint an accurate picture of the America that brought you the Kent State Massacre and the assassination of Harvey Milk.

This is not to belittle the work that still needs to take place in our nation. I only mean to demonstrate that it is possible to progress from that which once was.

This is why the muffled gasps of horror I hear when I mention travelling to Cambodia are so disconcerting to me. Friends and even Taiwanese co-workers raised immediate questions about my safety and the reasoning for travelling to such a…”developing country” as soon as I broke the news. My boyfriend even lovingly sent me a string of articles relaying past violent crimes committed against tourists in Cambodia for the days leading up to my travels.

I understand their trepidation about malaria. I could even understand their apprehension if it was tied to blood flukes that inhabit the human body after contact with contaminated water (see my previous post about my own slight hypochondria). But it seems as if most of their fears stem from an antiquated version of Cambodia, or of Southeast Asia in general. Back when Southeast Asia was all just a blob on a map called ‘Nam, a hell on earth, where we lost our strapping, young American soldiers to the Viet Cong or PTSD. And, for those more acquainted with history, mention of Cambodia sparked images of killing fields, the Khmer Rouge, and the genocide that left over a quarter of the country’s population dead or wounded from torture at the hands of their own countrymen.

America’s past is remembered as Leave It To Beaver, but Cambodia still cannot get out of the jungle.

With that being said, I want to qualify a few claims in the interest of honesty, and thus, tell the rest of my story.

The Cambodian genocide was an atrocity that the world must remember and learn from if we ever hope to break the cyclical unrest that rips nations and peoples apart at their seams.

While in Phnom Penh, we travelled to the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, commonly referred to as S-21, for a better understanding of this tragedy. The S-21 prison was a torture center for those political prisoners suspected of committing treason against the party. The building itself was once a high school, a center of learning for the community. Thousands saw the insides of this facility, but only seven of its prisoners survived.

The beginning of the museum opened up to a nice courtyard, a place for students to recreate and meet up with their friends after a long day of studies. But, for the over 17,000 Cambodians that entered this place as prisoners, this courtyard was their last glimpse of sunshine.

The museum itself was left mostly intact, providing visitors an accurate picture of daily life in the prison. There were iron beds in the torture rooms, where prisoners were beaten and subjected to unimaginable physical and psychological tortures for information.

One account states that centipedes were placed in the wounds and private parts of the female prisoners in order to make them talk. Some prisoners were manually emptied of blood, which was then given to the Khmer Rouge troops. For those that lost consciousness while being tortured, “medics” were sent in to pour salt water over wounds. This kept prisoners alive and conscious for as long as possible, so that confessions could be made. Once a prisoner “confessed,” he/she was systematically executed.

I write this because it is important that you know. I write this because it is true.

Interrogators were typically teenaged boys from the countryside, brought in to “smash the enemy.” For the young men employed at camps like S-21, this new and exciting dream of a strong, powerful Cambodia gave them something to believe in. These men were undereducated, predominately illiterate, and angry at the elite class for their urban wealth. Social change occurs when the undervalued, underappreciated and angry are empowered, a change that could be for the better or for the worse.

Pol Pot had a dream for their new Cambodia, a Cambodia of their past. He himself said, “Everything I did, I did for my country.”

But it was a dream of horrors, a deadly, sadistic dream. And in Cambodia, a museum has been erected to ensure that this history will never be allowed to repeat. It stands as a reminder and also as a warning.

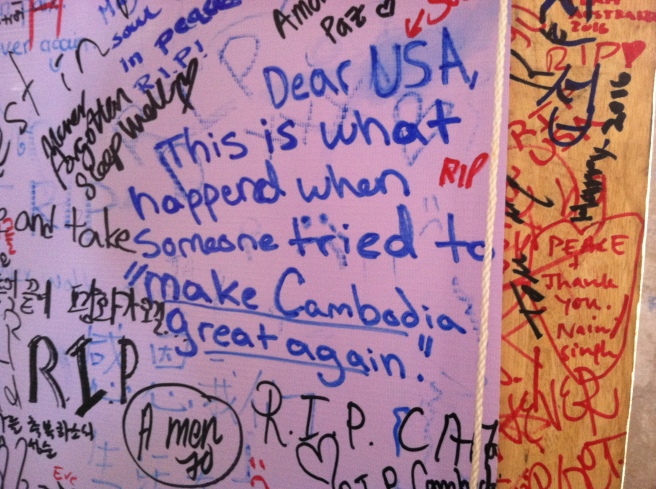

In graffiti on one of the back walls of the museum, it is written: “Dear USA, this is what happened when someone tried to ‘Make Cambodia Great Again.’”

Cambodia is now a nation bent on eradicating its once violent image in the eyes of the rest of the world. But instead of a country in militaristic and political desperation, a new, more subtle desperation seems to lurk.

This desperation seems to hang in the air, with the gusts of dust and grit kicked up from building projects that shoot up like weeds to sunlight. I see it in the eyes of every tuk-tuk driver that asks me, in decent English, where I wish to go.

I spent most of the beach portion of our trip contemplating this.

To appease my roommate, or more to convince him to take this trip with me in the first place, a tropical island beach was a necessary component of our little adventure. While breathtaking, beaches are generally not my favorite place to be, due to the inconceivable amounts of sand I find on my person once I remove my bathing suit in the shower. Magically, I find sand in every crevice and cranny on my body, as well as in every article of clothing and every bag that comes within a two-mile radius of the ocean. It is maddening.

To distract my mind from this granular ambush, I allowed my thoughts to trail off from the book that I was attempting to read. I took some time to evaluate my position here on Koh Rong, in Cambodia, and the reaction that the locals have toward tourists that visit their island and country, seeking one big party that never ends.

I had seen many Cambodian children playing in the glow of the neon signs of bars, of restaurants that serve food they cannot afford. Walking up and down the beach, I saw a building marked “Friends of Koh Rong,” an organization created to assist locals in the transition toward accepting the influx of tourists as an important part of their economy. I realize that this must bolster the revenue of the island considerably, but at what cost?

These children will only see one side of tourism: the party scene. They will watch as young foreigners sprawl out on their beaches, drinking until they make themselves sick, complaining when even the slightest detail varies from their tropical island fantasy.

However, now that they are here, the island relies on these people. The tourists bring in money from the outside world, money that they need to provide a living for their families. So, they are extra polite, and do not complain when they are treated disrespectfully. They learn many languages so that the tourists can get around with ease. They pour the alcohol and clean up at night, and this is how their lives are and will continue to be.

Our tuk-tuk driver in Siem Reap was with us for two full days. We stayed out until after sunset on the first day, and were up for sunrise the following morning. This was part of our two-day tour of the city of Angkor, where Angkor Wat is located. We spent somewhere between seventeen and twenty hours exploring temples in those two days.

It cost fifteen dollars to rent out the tuk tuk driver for an entire day. And that is not fifteen dollars a day per person. That is fifteen dollars total.

We pried a little more into his private affairs the more time we spent with him. He was a new father, his wife having just given birth to a beautiful baby boy three months ago. He needed the money and competition between tuk tuk drivers was fierce. He was overly polite and never accepted the snacks we offered him. And we felt so bad for him that we tipped him almost what he was charging to drive us around.

Similarly, in Battambang, we attended a cooking class taught by a Cambodian chef, something only the most touristy of tourists ever attempted. When Charlotte innocently asked if Khmer food (Cambodian food) could be spicy, a barely repressed storm seemed to cross the face of our instructor. He interrupted the lesson to explain to us that Khmer food is traditionally very spicy. However, when tourists come, they complain about the spice, and complain online about the restaurant itself. Because we all use Internet reviews to seek out places to eat, restaurants lose business for not catering to the Western palate. And this is why, he concluded, the Khmer you know is only a shadow of what it truly is.

These were the first and only traces of outright resentment that I detected from any Cambodian, but it left a cloud hanging over the rest of our lesson.

Almost every foreigner that I met along the trip couldn’t rave enough about the hospitality of the Cambodian people. They would bend over backwards for you, one tourist told me. And if you looked for that sort of thing, you could definitely find it. But I personally could not shake the feeling that this was not the full story here. That behind those pleasantries and group-discount rates is a tale of desperation, of surviving in a country whose economy leans heavily upon being of service to others.

Yet, even as Cambodia struggles in its postcolonial dilemma, the country radiates a resilience and vibrancy unique to its people and culture.

As I scaled the ancient stone steps of a temple in the city of Angkor, a gaggle of Cambodian boys laughed at my hesitancy. I had originally contented myself with watching others climb to the top, not afraid to climb up as much as I worried about getting back down. However, Eric’s mocking incentivized me enough to think only of my ascent, and straighten out the details of my descent later.

It was about halfway through the climb when I started to feel nervous. I perched on a nearby platform to regain my composure. The boys had been running through the temple grounds as if it were a semi-religious parkour, bounding through construction zones and off precarious ledges with ease. They saw my struggle and gave me time enough to make it three-quarters of the way to the top before they scaled the steps as a herd, reaching over and under each other to find footing and hold.

I watched with a maternal concern for their safety, and, when they caught sight of this worried reaction, the boys merrily grinned, as if goading me to finish my climb and give them a piece of my mind.

It wouldn’t have helped. They didn’t understand English.

One boy, sporting a purple athletic shirt, was particularly encouraging, barking at me in Khmer until I pulled my legs over the precipice and looked out to the world around me. But, of course, by that point he and his billy goat friends had already tired of this tiny molehill, and had bounded away in search of newer adventures.

They came back in time to watch my descent, and it was a real show.

I had to go down the steps backwards, resting my butt on every stair that I had conquered. Not even halfway down, the fear of falling rooted me in my spot, and Charlotte was forced to make all sorts of promises to charm me from the stone to which I clung. Once I was on solid ground again, I managed a small nod towards my worthy competitor, the stairs, only to spot the purple shirt out of the corner of my eye.

He had climbed up and down the stairs while I was wrestling with my overwhelming fear, but once I seemed calm again, the boy’s mouth became a straight line, and his childish features showed a hint of the man he would become as he nodded to me and darted up the ruins of his people’s history.

His somber expression might see him through many of the difficulties he encounters, growing up in Siem Reap, but his smile is distinctly Cambodian. Despite grave setbacks, the Cambodian people have found a way to remain hopeful about the future of their homeland.

I met many people whose diligence was inspiring. Mothers who sold handmade clothing to put their daughters through school. Young women working in hostels to practice their English. And with each conversation, I began to recognize it. A hope that many in my country seem to have lost.

This Fourth of July, who knows where I will be. Taiwan, Japan, or maybe even on a flight, headed home. But, regardless of my physical location, I will take a moment to remember what true belief in one’s country looks like. This hope in the future, this belief that things will, that things must get better, that is what will guide us as we push forward towards our goals. It is the most I can do for my country.

Inscription of Hope I believe in the sun even when it is not shining and I believe in love even when there's no one there and I believe in God even when he is silent I believe through any trial there is always a way but sometimes in this suffering and hopeless despair my heart cries for shelter to know somones there but a voice rises whithin me saying hold on my child I'll give you strength I'll give you hope just stay a little while I believe in the sun even when it is not shining and I believe in love even when there's no one there but I believe in God even when he is silent I believe through any trial there is always a way may there someday be sunshine may there some day be happiness may there someday be love may there someday be peace